Review: Toy Wars

“Increasingly, a small group of executives determined how the children of the world would play. … This is in the best interests of capital, not kids.” — author’s note.

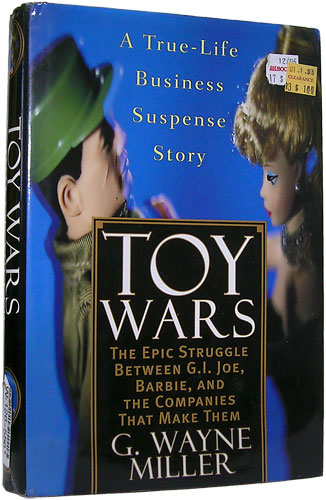

Despite toys being a USD67 billion market worldwide, the toy industry doesn’t get much mainstream coverage ordinarily. There was a flurry of reports during the recent safety scares and there’ll usually be an article or two whenever the larger toy companies announce their financial results but by and large, there’s little coverage and less scrutiny because it’s not seen as a beat that makes journalistic careers. It’s a pity because there are great stories to be told as G. Wayne Miller shows with his 1997 book, Toy Wars.

Miller approached Alan Hassenfeld, then the chairman and CEO of the world’s number one toy company, with the intention of spending two years writing a book about Hasbro’s crown jewel, G.I. Joe, the very first action figure and iconic boy’s toy. Miller took five years to write his book after realising there were bigger stories.

The business of play

There’s the story of the toy industry itself, a fiercely competitive fashion industry with fads that hit big and fade away quickly, and its move towards the stability of globally-recognised brands.

There’s the story of toy marketing, an inexact science. Despite throwing millions of dollars at advertising, despite heavy research and despite carefully monitored focus groups, some toy lines sell while others simply don’t. As noted in the book, only 28 out of the 257 action figure lines introduced between 1982 and 1993 would be deemed successful. This unpredictability is made apparent as the author recounts the history of G.I. Joe and its repeated rise and fall.

There’s the story of corporate mergers and takeovers as the toy companies seek growth through acquisitions. The videogame market slump of the 80s would see pedigreed toy companies mortally wounded and easy pickings for their greedy competitors.

There’s the story of ruthless number-crunching suits versus the creatives, the folks with the passion for the product. It’s an all too familiar tale of corporate politicking as the upper echelons jostle for power, money and prestige while the lower ranks look resentfully on. An ambitious suit complains his six-digit pay packet wasn’t sufficient remuneration even as a toy sculptor mournfully notes he couldn’t afford to send his kids to college.

There’s the story of Barbie, a powerful force unto herself. The reigning queen of the fashion doll industry, she would see off all pretenders to the crown. Hasbro alone would attempt and fail repeatedly to usurp her with challengers like Bobbie Gentry and the Flying Nuns, World of Love, Leggy, Charlie’s Angels, Jem, Maxie and Sindy. This fierce competition would eventually see toy company executives earnestly comparing doll breasts in a Dutch courtoom.

There’s the story of Margaret Loesch. She believed in a curious Japanese property called Dino Rangers at a time when no one else did. She would later staunchly defend the show as it came under attack from all fronts culminating in a congressional hearing.

The Brothers Hassenfeld

But Toy Wars is primarily a story about three generations of Hassenfeld brothers and Hasbro, the company they founded and helmed. It’s literally a rags to riches tale as the first generation of Hassenfeld brothers, immigrants escaping the pogroms in Eastern Europe, sold scrap cloth when starting out in the US. The second generation of Hassenfelds would introduce the world to toy classics like Mr. Potato Head and G.I. Joe. The third generation of brothers, Stephen and Alan, would transform Hasbro spectacularly into a modern Fortune 500 corporation and for a time, the world’s largest toy maker. It was a dizzying rise to greatness; if you had USD15,000 worth of Hasbro shares in 1982, you’d almost be a millionaire 12 years later.

But there are many downbeat stories at Hasbro recounted, too. Miller notes in his foreword some of the most painful moments he witnessed in two decades of journalism occurred within a toy company. Corporate reengineering and politicking would see loyal servants cut loose and factories shut down. For all the whimsy and playfulness, toy-making is still a business and a ruthless, unsentimental one at that. It all comes down to profitability targets and enhancing shareholder value. Fail to achieve your current targets and it doesn’t really matter how loyal you are, how long you’ve been at the company, what you’ve achieved in the past and how much you love what you do.

Kid Number One

The book’s protagonist is Alan Hassenfeld, the younger brother who never wanted to be CEO, who nevertheless successfully helmed Hasbro during tumultous years. This is a quirky man who wears rubber bands as bracelets, keeps lucky pennies in his loafers and describes himself as Kid Number One. This is also a man with an explosive temper who could reduce employees almost to tears, a man who ordered the corporate restructuring that would see long-term employees jobless and would cunningly battle Mattel’s hostile takeover.

The thing that ultimately stands out about Alan Hassenfeld is his integrity and humanity. The rubber bands are worn in memory of a teenaged love who died, he would insist Hasbro be socially responsible and he would even allow the author to continue with his warts-and-all book during the toughest years at Hasbro. This book could not have been written at any other company under any other chairman. The reader will end up being charmed by the man even as the author undoubtedly was.

If the book has a flaw, it is much too Hasbro-centric. Other companies are described cursorily and usually unflatteringly. Mattel notably comes across as ruthless and the reader will be led to associate the word “sharks” with the company. Though G.I. Joe is covered, other famous lines that bear the Hasbro logo are described with little or no depth. Transformers, for instance, is only mentioned in passing. But this is perhaps understandable. Miller started out with the intention of writing about G.I. Joe and spent five years at Hasbro so both would naturally end up providing the bulk of the material for the book.

Though it has been 11 years it was first published, Toy Wars remains an engrossing book about toys and toy makers as well as a notable look at the business of making and marketing playthings. It’s worth seeking out because there are a great many interesting stories to be told about the toy industry and far too few books to tell them.

Links

Toy Wars excerpt.

You may also order the book through the author’s site.

Business Week review.

“Some might say that the exposure of so much detail should be embarrassing to a company. But it is through these particulars that Toy Wars makes us care about one man’s struggle to shoulder the burdens of the corner office.”

New York Times review.

“The great sadness of this book is that there is so much agitation, angst and loathing inherent in the commerce of play. Countless toy executives dance across the stage and then depart, like the toy lines that jam retail shelves before they disappear.”

Yo Joe! interview with the author.

“Once inside Hasbro … I saw a much bigger drama involving Wall Street, Hollywood, and billions of dollars. I got to write all about Joe, with an access no other writer has ever had, but also some incredibly fascinating people …”

Writers Write interview with the author.

“While there were certainly zany moments, for the most part this is a rough-and-tumble business where billions of dollars are at stake and careers can rise and fall virtually overnight. And it was surprising the extent to which Wall Street dictates performance.”